Refugees and Asylum Seekers

A. Fishman, J. Quinones, S. Sandoval, and C. Velazco

Stories of Abuse: Vulnerable Populations in Florida’s Detention Center

Asylum seekers are treated like criminals by the U.S. immigration system, as they are often apprehended and held in prison-like detention centers while their pleas are evaluated. Holding migrants in detention centers is particularly prevalent in Florida, and as of 2019, “Florida held the sixth-largest population of people detained by ICE” (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2019). Many Florida detention centers are rife with abuse, and Homestead and Krome, both located in South Florida, are no exception.

Homestead

Figure 1: Homestead facility in Miami (Amnesty International UK, 2019)

Although those working at the Miami Homestead detention center for unaccompanied migrant children attempted to make the facility seem like a luxurious daycare, a look inside the complex tells a different story. Homestead, which first opened in 2016 as an emergency influx facility, was able to run the facility under minimal supervision, as it was the only children’s for-profit facility in America. This means that the shelter was exempt from following Florida’s child care standards. A lack of oversight meant that the Florida Department of Children and Families had no jurisdiction over Homestead, which created loopholes for them to hire staff that did not go through child-abuse background checks. This lack of vetting resulted in four sex-abuse claims, three of which were not investigated.

Interviews with the children held at Homestead revealed that children endured inhumane conditions. In 2016, a 17-year old, who feared being kidnapped by her father’s politically influential enemies, left Guatemala to seek asylum in the U.S. Instead of being released to relatives living in the U.S. while her plea was evaluated, she was forced to stay in Homestead, which her family referred to as a “child prison” (Iannelli, 2018).

Another child going by the alias Sofia, for safety concerns, shared her heartbreaking story. Sofia and her sister made the journey from her home near Pedro, Sula, “the murder capital of the world,” to the U.S., where they were separated. At Homestead, Sofia was ridiculed, as staff continually told her and other children that Hondurans would “make the place dirty.” She recalled a caretaker telling another child that she deserved “to be deported for intruding this country.” The hostile atmosphere and the absence of her family made living in the detention center unbearable. Additionally, Sofia shared that the children were under a no-touch policy, where they were unable to hug their own siblings (DeFede, 2019).

Krome

The history of Krome traces back to 1965, where the facility was originally built as a missile base for Cuba during the Cold War. When the Cold War subsided, Krome closed as a military base but reopened as a refugee detention facility in 1980 as a result of the Mariel Boatlift, which caused an influx of Cuban immigrants to the U.S. (Chardy, 2015).

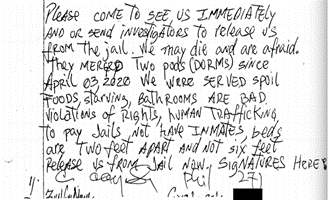

Figure 2: A statement signed by 100 detainees was sent to a Miami federal judge on April 16, 2020 (Madan, 2020)

Located at the edge of the Everglades, Krome has undergone much restructuring since its opening. Detainees live in dorm-like structures with televisions, and they have free access to make phone calls. Krome claims to have an updated health clinic with a substantial number of healthcare providers (Chardy 2015). These updates, however, do not mask the history of abuse that detainees of Krome have faced, including physical and verbal abuse, harassment, and death. Since 2003, 159 people have died. Luis Marcano, for example, died in 2018 after having complained of abdominal pain for a month.

Figure 3: Protesters calling for the shut-down of Homestead, 2019 (Kumpf, 2019)

This past January, Herby Yves Pierre-Gilles stated that an officer punched and kneed him, while two other guards ripped off his clothes and underwear. Freedom for Immigrants is currently calling for a thorough investigation. “I pray and hope that my situation will be brought to the public's attention so that a change can be made for the better," Pierre-Gilles said. There have also been four civil rights complaints since October 2020 against prison guards who have threatened, coerced, and used direct force against Black immigrant detainees.

Current Situation

After months of public pressure, and a court ruling that claimed children were being held in prison-like conditions, Homestead was shut down in 2019. Most of the children were reunited with their families; however, many of them still do not have sponsors, meaning that when they turn 18, they will be handcuffed and transferred to an ICE adult facility. Meanwhile, conditions in Krome have worsened due to COVID-19 since detainees who have not yet been tested are mixed with those who have tested positive. Additionally, there’s a shortage of hand-sanitizers and soaps. U.S. District Judge Marcia Cooke ordered ICE to release detainees and reach 75% of capacity since overcrowding violates detainees’ constitutional rights.

To find out more information and ways you can get involved, go to https://floridaimmigrant.org/

Sources

Allen, Greg. 2020. “Federal Judge Orders ICE To Release Detainees At 3 Florida Facilities.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/05/01/848681749/federal-judge-orders-ice-to-release-detainees-at-3-florida-facilities (February 17, 2021).

Burnett, John. 2019. “Inside The Largest And Most Controversial Shelter For Migrant Children In The U.S.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/2019/02/13/694138106/inside-the-largest-and-most-controversial-shelter-for-migrant-children-in-the-u- (February 17, 2021).

Cardona, Alexi C. 2021. “Advocates Demand Investigation Into Alleged Beating of Krome Detainee.” Miami New Times. https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/report-haitian-detainee-beaten-at-floridas-krome-detention-center-11848086 (February 17, 2021).

Cardona, Alexi C. 2021. “Advocates Denounce Biden Plan to Reopen Homestead Migrant Children's Facility.” Miami New Times. https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/biden-to-reopen-homestead-shelter-for-migrant-children-11881926 (March 3, 2021).

Chardy, Alfonso. 2015. “A Look inside Krome: from Cold War Base to Immigrant Detention Facility.” Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/immigration/article38001279.html (February 17, 2021).

Charles, Jacqueline, and Monique O Madan. 2021. Haitian detainee accuses Krome guards of attacking him. ICE asked to investigate. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/haitian-detainee-accuses-krome-guards-of-attacking-him-ice-asked-to-investigate/ar-BB1dxVFx (February 17, 2021).

DeFede, Jim. 2019. “Sofia's Story: Inside The Homestead Facility For Unaccompanied Minors.” CBS Miami. https://miami.cbslocal.com/2019/07/31/sofias-story-inside-homestead-facility-unaccompanied-minors/ (February 17, 2021).

Iannelli, Jerry. 2019. “Five Awful Stories About Miami's Child-Migrant Compound.” Miami New Times. https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/five-awful-homestead-miami-child-immigrant-camp-stories-10880065 (February 17, 2021).

Kumpf, Kristin. 2019. “What It Means That We Shut down Homestead Detention Center.” American Friends Service Committee. https://www.afsc.org/blogs/news-and-commentary/what-it-means-we-shut-down-homestead-detention-center (February 17, 2021).

Madan, Monique O. 2020. “Miami Federal Judge Publishes Letters Sent to Him by ICE Detainees.” Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/immigration/article243736647.html (February 17, 2021).

Madan, Monique O. 2020. “Sex Abuse Claims Revealed at Homestead Shelter, Where Staff Was Not Vetted for Child Abuse.” Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/immigration/article244244402.html (February 17, 2021).

“Prison By Any Other Name: A Report on South Florida Detention Facilities.” 2019. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/20191209/prison-any-other-name-report-south-florida-detention-facilities (February 17, 2021).

“The Senseless Detention of Children ... Is a Stain on the US Human Rights Record.” 2019. Amnesty International UK. https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/usa-authorities-florida-should-close-down-homestead-child-migrant-detention-centre (March 3, 2021).